HEALTHCARE SAVINGS TIED TO HEALTHY FOOD, NEW DATA DEMONSTRATES

LILO H. STAINTON | AUGUST 16, 2017

Food stamps do more than help seniors stave off hunger, they also help them avoid hospitals and nursing homes

There is little question good nutrition can lead to better health. But new research illustrates how, when it comes to low-income seniors, access to quality food can also save money by reducing the number and duration of hospital visits and nursing home admissions.

And several experts said that while the data was developed in Maryland, the results are still highly relevant in New Jersey — which has nearly 190,000 elderly residents with limited economic resources — and they urged the state to do more to connect vulnerable citizens with the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, as food stamps are now known.

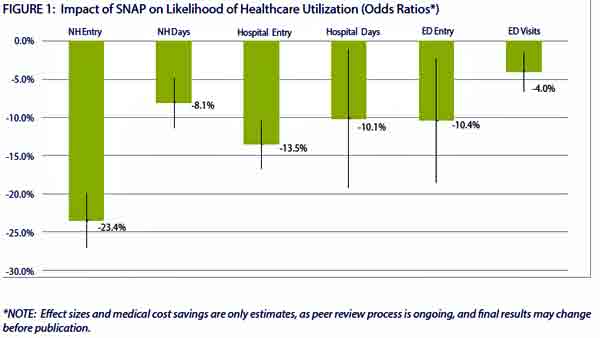

The study of elderly Maryland residents by Benefits Data Trust, a national nonprofit based in Philadelphia, found that participation in SNAP cut their odds of hospital admissions by 14 percent, reduced the need for emergency room visits by 10 percent, and cut their likelihood of going into a nursing home by nearly one quarter. It also led to an 8 percent to 10 percent drop in the number of days a patient who was admitted remained in one of these facilities.

Good food quantified

Further analysis by economists at Northwestern University determined that expanding SNAP benefits to all the eligible seniors studied would have saved $34 million in nursing home costs and cut hospital expenses by $19 million in 2012 alone. On average, better nutrition benefits would have cut medical costs by $2,100 per person, they found.

The study involved nearly 54,000 low-income seniors who received benefits through both Medicare and Medicaid. On average, the participants were 75 years old and had less than $6,000 in annual income. But while nearly all qualified for the income-restricted food stamp program, less than half were enrolled in the federal program administered by states and counties.

“This report is a real eye-opener,” said C. Brian McGuire, associate state director of advocacy for the AARP. “We were very aware of how important nutrition is to older people’s health, but this is the first time we’ve seen the impact quantified in terms of how access to food through SNAP impacts the use and cost of health care services.”

“Policymakers now can see that SNAP actually saves a huge amount of money, particularly by reducing hospital and nursing home admissions,” he said.

Ray Castro, a healthcare analyst with liberal think tank New Jersey Policy Perspective, which has long tracked social-service policy in the Garden State, agreed the study provided a “compelling reason” for state and federal governments to protect and enhance the program.

Low SNAP participation

Castro stressed that BD Trust’s findings would likely apply here too. “New Jersey has consistently ranked among the states with the lowest SNAP participation rates and outreach,” he said.

“We have always known that in addition to providing nutritional assistance, SNAP stimulates the economy and increases jobs. This study now also documents the enormous health benefits that result from SNAP,” Castro added.

As of May, New Jersey provided SNAP benefits to nearly 791,300 individuals, according to the state Department of Human Services, which administers aspects of the program; this is down 8 percent over the previous year. The program is open to individuals who earn less than $22,000 a year, or nearly $37,300 for a family of three.

While the DHS does not track residents who are eligible, but not enrolled, other studies suggest the program is not reaching everyone who could be helped. A report based on 2014 data and released in January by the United Way found that 37 percent of state residents — or nearly 1.2 million people — struggled to afford basic necessities. According to state reports, in May 2014 the SNAP program reached more than 887,000 individuals and was growing.

Poverty and poor health

According to the BD Trust research, conducted with help from other data analysts, experts at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, and officials from Maryland’s health and human services departments, there is plenty of research that shows poverty and food insecurity lead to poor health outcomes. SNAP has also been proven to address one of these issues.

One study found up to 40 percent of health outcomes are tied to social factors. But much less is understood about how that translates into healthcare use and costs, something that has become a major focus in healthcare policy. (According to their research, the average annual cost for a hospitalization was more than $25,000 and nursing home stays cost more than $28,000.)

“There is growing understanding that to achieve the goals of improving health outcomes and controlling costs, the healthcare sector must tackle the social determinants of health more directly,” the authors wrote. But despite that consensus, “relatively little is known about whether specific non-medical interventions can positively impact health outcomes and associated healthcare costs, particularly among low-income seniors and other high-utilizers.”

BD Trust, which runs a half-dozen programs to help connect low-income residents with SNAP and other benefits in a handful of states, urged states to adopt policies that maintain and boost enrollment in the food stamp program — enacting regulations to keep eligible individuals involved year after year and better coordinating various data sources to identify those who are eligible but not participating.

The group also encouraged the federal Department of Agriculture, which oversees the program, to streamline the application process and requested that Congress maintain or expand funding.

Castro, with the NJPP, said Gov. Chris Christie has recently taken a different tack, vetoing language in the annual budget he approved in July that would have restored so-called “heat and eat” benefits that made it easier for SNAP participants to also receive help paying heating bills. (The governor blocked a similar attempt last year.) As a result, some 160,000 Garden State residents have seen their SNAP benefits dip by about $90 a month, the group found.

The outcome of these policy lapses, Castro said, is “you have perfect storm that results in too many seniors going hungry.”

Republished from NJ Spotlight. For the original article, click here.